“The fundamental reason for the pre-eminence of Islamic civilizations lay neither in accidents of history nor in acts of war, but rather in their ability to discover new knowledge, to make it their own, and to build constructively upon it. They became the Knowledge Societies of their time…The spirit of the Knowledge Society is the spirit of Pluralism—a readiness to accept the other, indeed to learn from him, to see difference as an opportunity rather than a threat.”

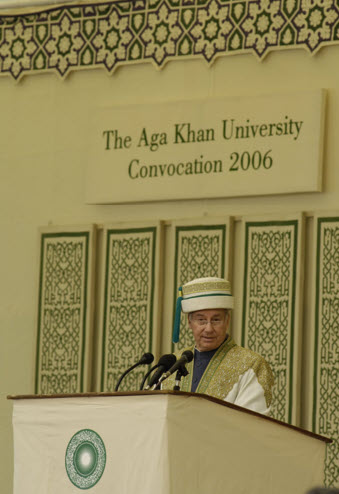

Mawlana Hazar Imam Aga Khan IV

Aga Khan University Convocation, Karachi, 6 December 2006

Speech

In pre-Islamic times, the recitation of poetry was the mark of artistic achievement. The prevalent form was the qasida – a long monorhyme (aa, ba, ca) that was used in praise of someone or basic rhetoric. Subsequently, it was used to teach morals as well as praise God and the Prophet.

An important aspect was the growing awareness of the potential expressiveness of the human voice, considered a reflection of the soul’s mysteries and feelings. As Islam spread, the music of the various communities became entwined with the traditions of the conquered lands.

For the first three centuries after the emergence of Islam, Medina became a musical centre in the Arabian peninsula attracting talented artists. This was noted in some of the earliest surviving works on music including the Book of Melodies by the esteemed poet Yunus al-Katib (d. 765), Book of Diversion and Musical Instruments by Abu’l Qasim Ubayd Allah (d. 911), and Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems by al-Mas’udi (d. 956). In his Book of Songs, one of the most celebrated works in Arabic literature, the poet and historian Abu’l-Faradj al-Isfahani (d. 967) compiled a collection of poems from the pre-Islamic period to the ninth century, all set to music along with biographical details about the authors, composers, and singers. He noted that “in a society avid for knowledge the study of music became obligatory for every learned person; music was one of the topics frequently discussed by people in all walks of life ” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 26).

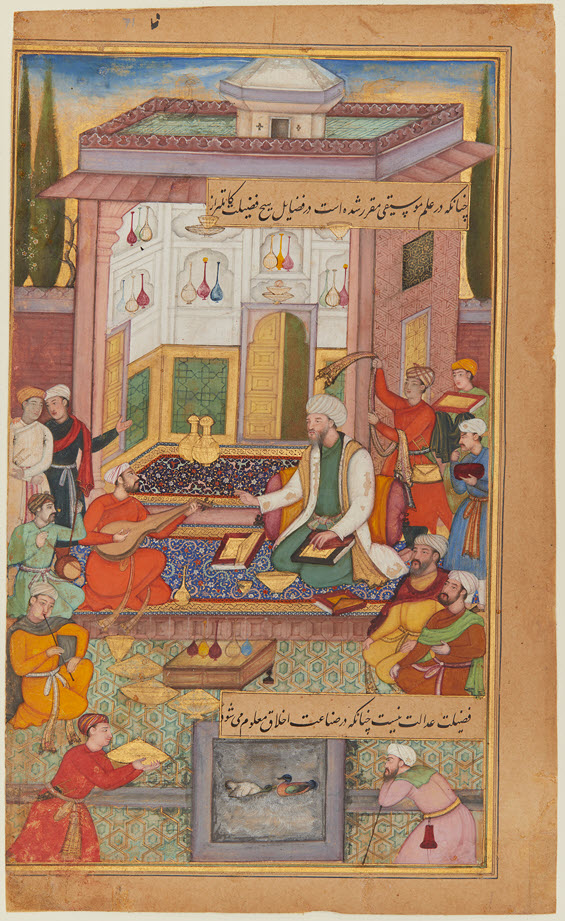

In Islamic civilisations, music was among the mathematical sciences which included geometry, astronomy, and logic, and considered an important means of attaining philosophical and spiritual knowledge. The lute, which was the standard tool for demonstrating tuning, had four strings corresponding to the natural phenomena: the highest representing fire, the second representing air, the third representing water, and the fourth representing earth.

The combination of four also represented the four seasons beginning with spring. The dimensions of the strings “are articulated not as measurements but as proportions: the relationship of breadth to depth” (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity, On Music, p 32) also representing the relationship of the cosmos to the earth and to the various celestial bodies, in harmony, according to divine creation.

Early Muslim intellectuals “were not able to disengage knowledge of the cosmos from knowledge of God or from knowledge of the human soul” (Nasr, Sufi Essays p 113). The primary focus was on the nature of things, “describing and explaining the three fundamental domains… God, the universe, and the human soul. The universe and the human self are viewed as inseparably linked” (Chittick, The Muslim Intellectual Heritage p 108-109).

[See The first revelation to the Prophet was about knowledge]

Ya’qub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (d. ca. 870), a philosopher, mathematician, physician, and musician stated that the mathematical sciences “prepare the student for higher studies of philosophy and for knowledge of the wonders of creation…The science of harmony in its broadest sense is central for understanding the complex network linking music to all attributes of the universe” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 49). In his work Book of Sounds Made by Instruments Having One to Ten Strings, al-Kindi explains that instruments help create harmony between the soul and the universe. Similarly, the Ikhwan al-Safa, in their Rasa’il on music noted that music “reflects the harmonious beauty of the universe… Musical harmony conceived according to the laws of the well-ordered universe helps man in his attempt to achieve spiritual and philosophical equilibrium…” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 50).

The prose writer al-Djahiz (d. ca. 868-9), in his masterpiece the Book of Animals, discusses the “characteristics of sounds and the effect of music on the souls of men and animals (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 25).

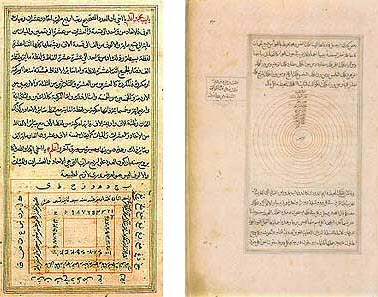

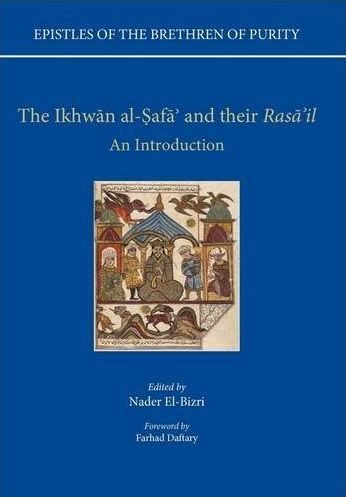

Al-Kindi’s theory was further developed by the Ikhwan al-Safa (Brethren of Purity), an anonymous tenth-century group of authors based in Basra and Baghdad, Iraq, who compiled an encyclopedic work – Rasa’il Ikhwan al-Safa’ (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity). Seeking to show compatibility of Islam with other religions and intellectual traditions, the Ikhwan drew on diverse schools of wisdom including Babylonian, Greek, Persian, and Indian traditions.

The Ikhwan occupied a prominent position in the history of scientific and philosophical ideas in Islam owing to the wide intellectual reception and dissemination of diverse manuscripts of their Rasa’il.

Although the exact date of the Rasa’il and the identities of its authors remain a mystery, some historians situate this brotherhood to the eighth century, attributing the compiling of the Rasa’il to the early Ismaili Imams Jafar al-Sadiq, Abd Allah (Wafi Ahmed), or his son Ahmad b. Abd Allal (al-Taqi); others situate the Ikhwan to just before the founding of the Fatimid dynasty in North Africa in 909. Daftary notes that the Ismaili origin of the Rasa’il was recognised by Paul Casanova in 1898, “long before the modern recovery of Isma’ili literature” (Daftary, The Ismai’ilis their History and Doctrines p 246).

“It was during the latter part of the nineteenth century that Western scholars first began to take a serious interest in the Ikhwan al-Safa’ and their Rasa’il. Among the leading contributors in the West to the study of the Rasa’il was the German scholar Fr. Dieterici who, for some thirty years, published texts and studies on Islamic philosophy with the Ikhwan al-Safa as the main subject of his attention. And it was Dieterici who translated the entire corpus of the Ikhwan al-Safa into German for the first time” (IIS).

In the section on music, the Ikhwan discuss that “musical tones [naghamat] have a spiritual effect on souls” (Epistles, “On Music,” p 84). Music, notes the Ikhwan, “reflects the harmonious beauty of the universe… Musical harmony conceived according to the laws of the well-ordered universe helps man in his attempt to achieve spiritual and philosophical equilibrium…the proper use of music at the right time has a healing influence on the body” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam, p 50).

The Persian physician Ibn Sina (d. 1037), in his monumental encyclopedic work Qanun fi’l-tibb (Canon of Medicine), discusses a special relationship between music and medicine that recurs in Arabic and European texts as late as the nineteenth century. The treatise on music in the Rasa’il also includes a theoretical contribution to the study of sound, the science of rhythm, and the science of instruments.

[The Canon of Medicine), which was translated into Latin by Gerard of Cremona in the 12th century and remained part of the standard curriculum for medical students until the late 17th century (Library of Congress)].

In his work The Ethics of Nasir, a philosophical treatise on ethics, social justice, and politics, the Persian philosopher Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (d. 1274) proclaims that after the nearness to God, ‘no relationship is nobler than that of equivalence as has been established in the science of music’ (Spirit & Life Catalogue p 167).

[Further Reading: Music in Ginans]

“The great medieval Arab philosophers, many of whom were also music theorists and even talented musicians, had a profound understanding of the power of sound to affect the human psyche and emotions. We are the heirs of their knowledge…Exposure to different ways of making music and thinking about music represents a form of enlightenment.”

Prince Amyn Aga Khan

Aga Khan Music Awards Ceremony, Muscat, Oman, 29 October 2022

Speech

Sources:

Amnon Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam, Wayne State University Press. Detroit.1995

Farhad Daftary, The Isma’ilis: Their History and Doctrines, Cambridge University Press, 1990

Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Sufi Essays, State University of New York Press, 1972

Epistles of the Brethren of Purity, “On Music,” Edited and Translated by Owen Wright, Oxford University Press, 2010

From the Manuscript Tradition to the Printed Text: The Transmission of the Rasa’il of the Ikhwan al-Safa’ in the East and West, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Contributed by Nimira Dewji, who also has her own blog – Nimirasblog – where she writes short articles on Ismaili history and Muslim civilisations. When not researching and writing, Nimira volunteers at a shelter for the unhoused, and at a women’s shelter. She can be reached at nimirasblog@gmail.com

Nice historical post.

LikeLike

What great article, meaningful scholarship.

LikeLike