In the tenth century, Ismaili Imams established a state in North Africa (from 909) and later in Egypt (973–1171), who claimed descent from the Prophet Muhammad through Imam Ali, and derived their name from the Prophet’s daughter, Fatima. During the Fatimid period, often referred to as the “golden age” of Ismailism, Ismaili thought and literature attained their summit. Cairo became a flourishing centre of scholarship, commerce, and the arts. After the fall of the Fatimid Empire, the community established the state of Alamut in 1090 in Persia (modern-day Iran), which fell to the Mongols in 1256.

Image: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

The first five centuries after the fall of Alamut represent the longest period of obscurity in the history of the Nizari Ismailis. The community was deprived of central leadership of the Imams, who had to go into hiding to avoid persecution, and remained inaccessible to the community for almost two centuries. The community scattered over a wide region from Syria to Persia, to Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. They developed independently, elaborating their own religious and literary traditions. During much of this period, the Nizaris guised themselves as Sufis, without actually associating with any of the Sufi tariqahs that were spreading widely in Persia and Central Asia. The Persian Nizaris appeared as a Sufi tariqah, using the master-disciple (murshid-murid) terminology of the Sufis.

By the middle of the fifteenth century, the Nizari Imams had established themselves in the village of Anjudan, in Central Persia, initiating a revival in Nizari Ismailism. During this period, with the adoption of Twelver Shi’ism as the official religion of the State, the Nizari Imams and community in Persia reduced their guise practices; the Imams began to consolidate the activities of the community particularly in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent.

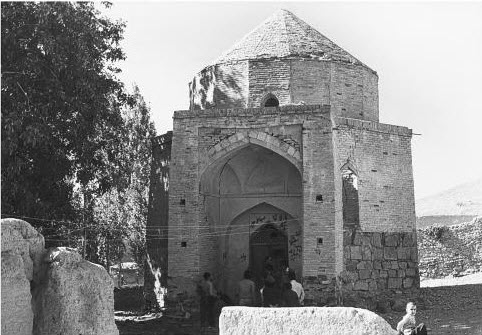

The Anjudan period also witnessed a revival in the literary activities of the Nizaris in Persia, where authors such as Abu Ishaq Quhistani (d. after 1498) and Khayrkhah Harati (d. after 1553) produced the earliest doctrinal works of the post-Alamut period. Khayrkhah’s few surviving works are valuable for understanding the revival in post-Alamut Nizari Ismailism and the contemporary Nizari doctrines. Valuable details are also preserved in the Pandiat-e javanmardi containing the guidance of Imam Mustansir bi’llah II (d. 1480) or one of his descendants. The mausoleum of Imam Mustansir bi’llah II is still preserved in Anjundan today in an area called Shah Qalander, the Sufi name by which Imam Mustansir bi’llah was known.

Farhad Daftary, Khayrkhah Harati: Nizari Ismaili da‘i, author, and poet (15th-16th CE centuries) The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis An Illustrated History

Research by Nimira Dewji

Be the First to Know – Join Ismailimail

Be the First to Know – Join Ismailimail

Get breaking news related to the Ismaili Imamat, the world wide Ismaili Muslim community and all their creativity, endeavors and successes.

Inspired? Share the story

Want to inspire? Send your stories to us at Ismailimail@gmail.com

Subscribe and join 18,000 + other individuals – Subscribe now!

Earlier & Related – Nimira Dewji at Ismailimail Archives:

- Mawlana Shah Karim: “The relationship between the Imam and his Jamat is a deep and continuing bond”

- Mawlana Hazar Imam was gifted manuscripts on architecture of Andalusia, a Knowledge Society of its time

- Mawlana Hazar Imam Designates Ismaili Center Houston as Darkhana for US Jamat, the ninth Darkhana

- Imam Hasan ala dhikrihi’l-salam appointed Sinan as his deputy in Syria

- The arts of the Fatimids, Mawlana Hazar Imam’s ancestors, continue to inspire

![[Music in Islam] Is listening to music unlawful?](https://ismailimail.blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/music-in-islam.jpg?w=150)