Continued from previous article

https://ismailimail.blog/2024/06/18/fabricated-tales-based-on-fear-and-ignorance-instigated-hostility-towards-the-nizari-ismailis-1-2/

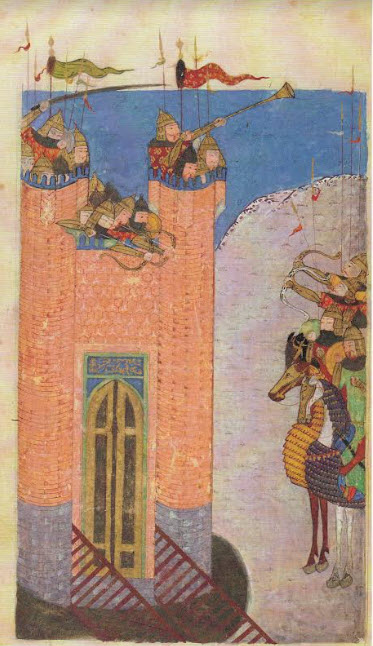

In 1256, Alamut collapsed under the onslaught of the Mongols, and in early 1270s, the Syrian fortresses surrendered to the Mamluks, who also successfully reduced the territories of the Crusaders. Henceforth the Nizaris lived discreetly in order to escape persecution. Under such circumstances, the Europeans had less reason to write about them; Westerners remained unaware of their existence until the early nineteenth century, when the Nizaris were re-discovered in Syria.

Nineteenth Century

The legends were erroneous revived by Marco Polo, who travelled across Persia, Central Asia, and China, commissioning the writing of his travelogue, while in prison in Venice, to a fellow prisoner Rusticello or Rusticiano, “a man of some literary talent and evidently a professional romance-writer” (Daftary, The Assassin Legends p 109). By the time Polo had been released from prison three years later, “Rusticello had completed what may be regarded as the original version of Marco Polo’s travels… The complex problems related to the authenticity of the manuscripts of this famous travelogue have been analysed by Sir Henry Yule (1820-89), H. Cordier (1849-1925), Arthur C. Moule (1873-1957)” (Ibid). ” Several scholars highlight the discrepancies in the travelogue. Dr Frances Wood, former head of the Chinese Department at the British Library (retired 2013), argues that Marco Polo never went to China. “There is absolutely no record of Marco Polo in the Yangzhou gazetteers of the period. Polo’s credentials are not corroborated with historical documents” (Association for Asian Studies).

“All the early manuscripts of Marco Polo produced during the fourteenth century have several omissions and revisions. Marco Polo himself seems to have revised his travelogue during the latter part of his life.” His accounts about Assassins “are traceable to Burchard, Arnold of Lubeck, and James Vitry … (Daftary, The Assassin Legends p 109-115). He coined the term ‘Old Man of the Mountain’ to Hasan Sabbah whereas the term was originally applied by the Franks to Rashid al-Din Sinan, the leader of the Syrian Ismailis of the Alamut period.

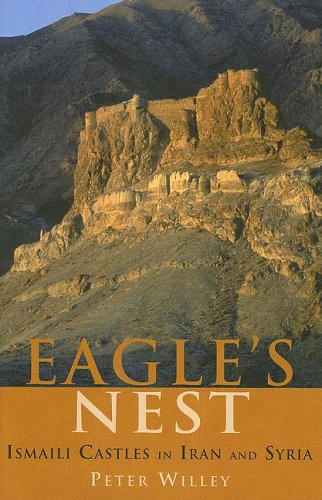

Sources agree that Marco Polo’s account of these legends “represents an original admixture of some details heard in Persia and the legends…then circulating in Europe, to which he added his own imaginative component in the form of the Old Man’s secret ‘garden,’ of paradise. And this ‘garden,’ not found in any earlier European source before Marco Polo, was essentially modelled on the Quranic description of Paradise then available” (Ibid. p 117). “However,” states Willey “the Ismailis have interpreted the Quranic description of Paradise esoterically, therefore would have regarded its literal embodiment on earth with a great deal of skepticism” (Eagle’s Nest p 55).

Although he seemed aware of the connection between the Persian and Syrian ‘Assassins,’ Marco Polo, never met the fida’is or the Old Man of the Mountain. He claimed in his writings, to have studied this community in depth where he had seen a ruined castle and had been told some local tales about the Nizari Ismailis. Polo was “likely to have adopted the various legends that had gained currency in the West and synthesised them into an elaborate account (Daftary, The Assassin Legends p 117).

By the middle of the fourteenth century, the word assassin, instead of signifying the name of a sect in Syria, had become a common noun describing a professional murderer. The first western [treatise] devoted entirely to the history of the Nizaris was published in France in 1603 by Denis Lebey de Batilly, a French official at the court of King Henry IV of France…. [he] set out in 1595 to compose a short treatise on the true origin of the word assassin… and the history of the sect to which it had originally, calling these sectarians ‘les anciens Assassins.’…. [but] it did not add any new details to what had been known in Europe…” (Ibid. p 121).

By the late fourteenth century, numerous manuscripts of Marco Polo’s travelogue were circulating in Europe in many languages including Latin, French, and Italian dialects. His version of the legends were adapted by successive generations of Europeans as the standard description of the Assassins. The earliest European account of the ‘Assassins’ based almost entirely on Marco Polo is the account of Odoric of Pordenone (d. 1331), the Franciscan friar from northern Italy and another famous European traveller who visited China during 1323-7, although Odoric claims to be relating his own observations:

“And in this country there was a certain aged man called Senex de Monte [Old Man of the Mountain], who round about two mountains had built a wall to enclose the said mountains…”

(The Journal of Friar Odoric, cited by Farhad Daftary in The Assassin Legends p 117)

The French orientalist d’Herbelot (1625-29) did compose a pioneering work on the Ismailis as one of the denominations of Shi’i Islam. Other memoirs were published, based on works of previous works, but continued to have erroneous accounts of the legends. Silvester de Sacy (1758-1838), in his Memoir, showed that the word ‘assassin’ was connected to the Arabic hashish. However, he partially endorsed the existing legends, which “under his authority were re-introduced into the orientalist circles of Europe.” The most widely read book at this time was by the Austrian Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774-1856) in which he too, “accepted Marco Polo’s account in its entirety as well as the sinister acts and heresies attributed to the Nizaris” (Ibid. p123 ). After all, these legends had been circulating for seven centuries

Juwayni’s account of Alamut

The anti-Ismaili war-historian Juwayni, who inspected Alamut after its surrender to the Mongols in 1256, was greatly impressed by its library, water-cisterns, and storage facilities, but he makes no mention of any delectable garden or sumptuous palace inside or outside the castle.” (Willey, Eagle’s Nest p 55). He inspected the library at Alamut before its destruction, selecting a few items for his own collection including Hasan Sabbah’s biography, burning the rest of the books. He recounts:

“I went to examine the library from which I extracted whatever I found in the way of copies of the Qur’an and other choice books … I likewise picked out the astronomical instruments such as kursis (part of an astrolabe), armillary spheres, complete and partial astrolabes, and others that were there. As for the remaining books, which related to their heresy and error, and were neither founded on tradition nor supported by reason, I burnt them all.” (From Juwayni’s History of the World Conqueror, p 639 cited by Willey in Eagle’s Nest p 81).

Juwayni tells us that the Saljuq offensive against Alamut was maintained for eight successive years.

Willey states “inseparable from these castles and the communities they supported are startling legends about the so-called Assassins who swept down from their [rugged] fortresses to target their enemies in doing, guerilla-style raids. Their leader Hasan Sabbah became notorious in the medieval European imagination as the charismatic ‘Old Man of the Mountain’ [a term originally used in reference to Rashid al-Din Sinan, the Nizari Ismaili leader in Syria]. He and his followers were demonized by the propaganda of the hostile Muslim majority – and by subsequent western embroidering – as terrorists and criminals” (Eagle’s Nest – inside front flap).

Ismaili Studies

The recovery of Ismaili manuscripts, preserved in private collections in Yaman, India, Persia, Syria, and Central Asia greatly facilitated the progress in Ismaili studies, allowing scholars “to evaluate critically different categories of non-Ismaili sources, dealing with the Ismailis including the Crusaders’ sources. The breakthrough has been particularly rewarding in the case of Nizaris of Alamut period whose history had been shrouded in so much obscurity, providing a suitable ground for imaginative tales…” (Daftary, The Assassin Legends p 124).

The pioneering work of Wladimir Ivanow (1886-1970), Marshall Hodgson (1922-68), and Bernard Lewis, revealed that “the Nizaris of the Alamut period who patronized learning … can no longer be judged as an order of drugged assassins for senseless murder and mischief” (Ibid).

Willey states

“we must never forget that the underlying military strategy of the Ismailis was of necessity defensive rather than offensive. This policy was imposed by the fact that the Ismailis were everywhere a small persecuted minority … Ismailis have always been, first and foremost, a religious community and not a military order… like their Fatimid forebears in Egypt, the Nizaris of Iran and Syria cultivated an intellectual and spiritual life of a high order in their mountain strongholds. Among the first things Hasan established at Alamut were a mosque and a library, which became the nucleus of a training centre for the da’is…“ (Eagle’s Nest p 62-63), who learned philosophy, languages, theology, history, and the Quran. The library, which was a renowned one, contained not only books, but scientific tracts and instruments.

According to Marshall Hodgson, the Ismailis society of the Alamut period

“was not a typical mountaineer and town-society … what was most distinctive was the high level and intellectual life. The prominent early Ismailis were commonly known as scholars, often as astronomers…at the main centres at least, were libraries…which were well known among Sunni scholars. To the end the Ismailis prized sophisticated interpretations of their own doctrines and were also interested in every kind of knowledge which the age could offer” (quoted by Willey in Eagle’s Nest p 61-68).

Valerie Gonzales states:

Old myths are very difficult to deconstruct, even when historical evidence reveals the absurdity of their foundations. The infamous “assassin” legend that from the Middle Ages soils the memory of the Nizari Ismaili community is an example of this incorrigible defect of the collective consciousness. The image presented by both Christian and Muslim chroniclers of the Ismailis as unscrupulous terrorists is unfortunate if their sole fault lay in surviving as a distinct political and religious community within a hostile and troubled environment. The Crusaders, Sunnis and Seldjuk Turks naturally saw in this Shi’ite minority a threat to their establishment and extended great efforts in eliminating the Ismaili State from Iran and Syria. In addition to the pressures exerted by the great powers holding sway over the Middle East, in the 13th century, the Ismailis had to confront the Mongol threat, which finally overwhelmed them. It is not wonder that in such a context they deployed the most efficient means of defense available to maintain not only the network of their strongholds and basis of their State, but also their faith and culture, the very sense of existence. In practice, however, they were no more immoral or cruel than their contemporaries. They simply proved tremendously clever and obstinate in facing adversity and in struggling against forces vastly more powerful than their own. And it is probably for this reason that the Nizari Ismaili community were subject to demonization.“

OpenEdition Journals

Late Peter Willey spent over forty years making more than twenty expeditions to Iran studying archeological remains of the fortresses of the Alamut period, documenting his findings in Eagle’s Nest.

Willey states:

“At the beginning of my work I had accepted more or less the conventional version of the ‘Assassins’ as a group of fanatic and somewhat rough and ready adventurers, led by their charismatic leader Hasan Sabbah, who established their power-base by building strong and well-supplied castles in the valley of Alamut and elsewhere… Once I had the opportunity of seeing for myself the very high quality of military architecture exhibited in their castles, which in many ways surpass the achievements of the Crusaders, I began to develop a greater appreciation of this remarkable community and the nature of the state they once created and defended, often against overwhelming odds, in the remote mountains of Iran and Syria for more than 150 years….

In contrast to the malevolent view of the Ismailis held by their opponents, we can now positively assert that they were a people of exceptional intelligence and determination with a sophisticated knowledge of military architecture, administration and logistics, as well as being highly successful agriculturalists and water engineers in a mostly arid and mountain terrain…. The picture that finally emerges is the very opposite of the ‘assassins’ and ‘terrorists’ popular imagination” (Eagles’ Nest p xxiii-xxiv).

Sources:

Antonino Pollio, The Name of Cannabis, National Library of Medicine

Farhad Daftary, A Short History of the Ismailis, Edinburgh University Press, 1998

Farhad Daftary, The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Isma’ilis, I.B. Tauris, London, 1994

Nadia Eboo Jamal, Surviving the Mongols: Nizari Quhistani and the Continuity of the Ismaili Tradition in Persia, I.B Tauris, New York, 2002

Nasseh Ahmed Mirza, Syrian Ismailism: The Ever Living Line of Imamate, Curzon Press, 1997

Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, I.B. Tauris, London, 2005

Contributed by Nimira Dewji, who also has her own blog – Nimirasblog – where she writes short articles on Ismaili history and Muslim civilisations.