“From time immemorial, small and oppressed minorities have had to be given a bad name – and in the Middle Ages the Ismailis were such a minority, fighting for their lives and their rights. Their oppressors had given them a bad name; they associated the Ismailis with the manufacture and use of the drug hashish, and it was alleged that they were addicts, the bad name, thus invented, stuck.”

Mawlana Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III

The Memoirs of Aga Khan World Enough and Time, Cassell and Company Ltd. p 67 footnote 1

Ismailis have been judged almost exclusively based on hostile accounts of their Muslim enemies and fanciful tales of the Crusaders. Consequently there were numerous misconceptions about the teachings and practices of the Ismailis, who came to be known by the misnomer ‘Assassins’ a term of abuse derived from the Arabic word hashish, for the hemp plant Cannabis sativa (Latin). The plant has been used, since ancient times, as textile fibre as well as in folk medicine to treat a number of ailments such as epilepsy, asthma, rheumatism, among numerous others (National Library of Medicine). It is not known how and when the Arabic word, which originally meant ‘dry herb,’ came to be applied to the person (or persons) using the product (Daftary, Assassin Legends p 90-91).

The use of hashish was widespread in Muslim regions during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, at which time its harmful effects were being addressed. Muslim writers sated “the extended use of hashish would have extremely harmful effects on the user’s morality and religion, relaxing his attitude towards those duties such as praying and fasting. As a result the hashish user [hashishi] would qualify for a low social and moral status, similar to that of a mulhid, or heretic. It was in this sense of ‘low class rabble’ or ‘irreligious social outcast’ that the term hashishiyya seems to have been used in reference to the Nizari Ismailis” (Ibid. p 91-92).

The term hashishi was used in Mustalian Fatimid writing

The earliest work referring to the Nizari Ismailis as hashishi was by the Mustalian Fatimid court of al-Amir, without any explanation, to refute the claims of Imam Nizar to the Imamat following the death of Imam Mustansir billah I (r.1036-1094). This implies that the term had already acquired a generally-known meaning by the early twelfth century.

[Upon the death of Imam Mustansir bi’llah, the dispute over his successor the community split into Mustaliyya (named after Mustali) and Nizariyya (named after Imam Nizar, designated by Imam Mustansir billah as his successor].

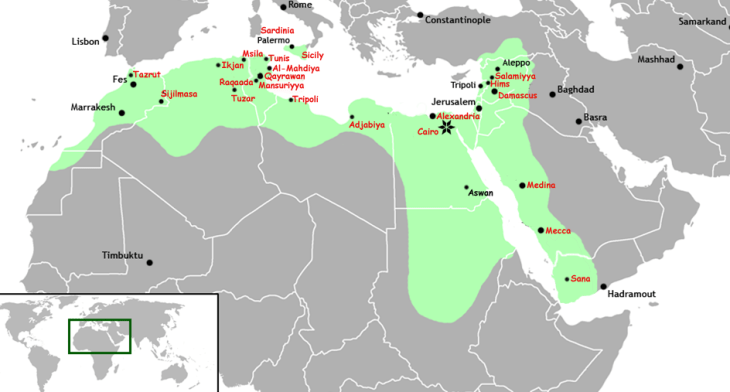

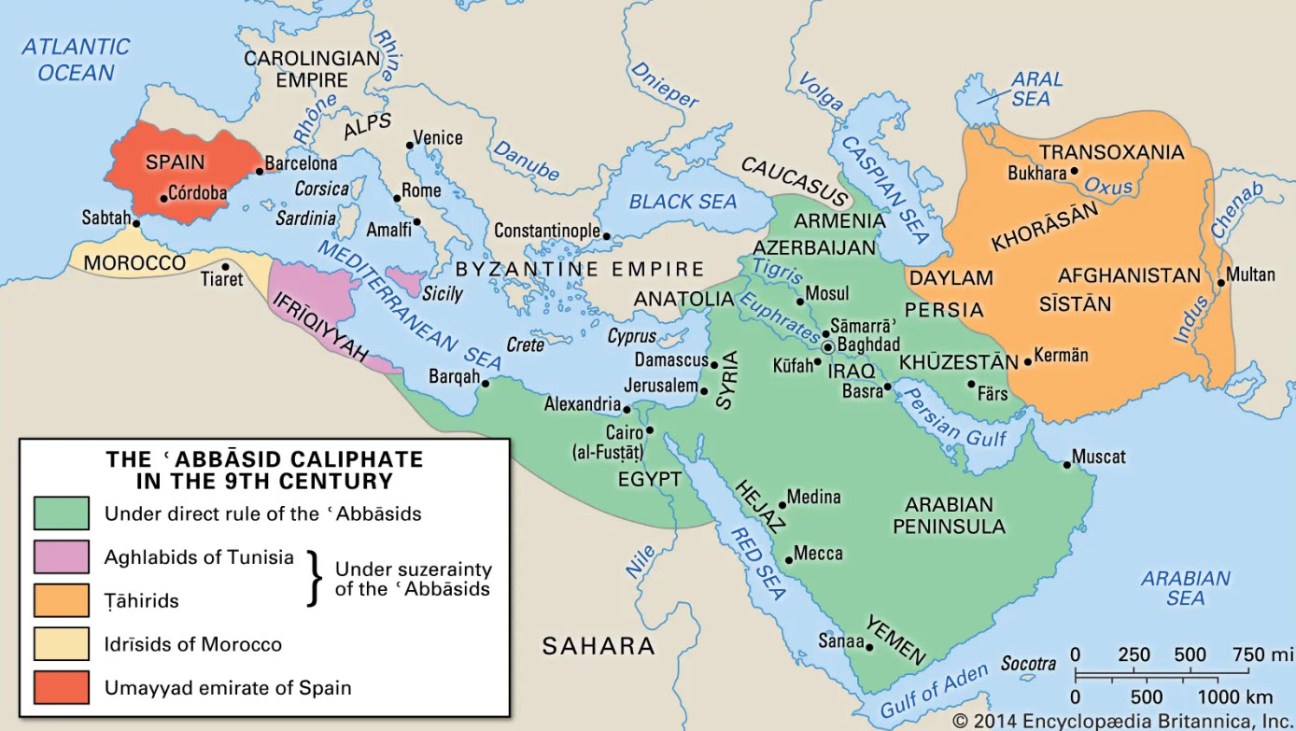

Following the founding of the Shi’i Fatimid caliphate (909-1171) in opposition to the Abbasids (750-1258), the Sunni establishment launched an anti-Ismaili campaign to discredit the entire Ismaili movement condemning them as malahida, heretics, or deviators from the true religion. Theologians, jurists, and historians were commissioned to fabricate the necessary evidence to support the Ismailis on specific doctrinal grounds detailing accounts of “sinister objectives, immoral doctrines, and libertine practices …while refuting the Alid genealogy of the Ismaili Imam. The Sunni authors, who were not interested in studying the internal divisions of Shi’ism, also blamed the entire Ismaili community for the atrocities perpetrated by the Qarmatis of Bahrayn,” including the stealing of the black stone from the Ka‘ba – which were then attributed to the Ismailis. This act caused the Abbasids public embarrassment and ultimately resulted in the first Sunni polemics against the Ismailis (Daftary, A Short History of the Ismailis p 10).

[Qarmatis split off from the Ismailis in 899, denying the continuity of the Imamat believing that the seventh Imam Muhammad b. Ismail remained their final Imam who was to appear as the Mahdi]

Among those commissioned was the theologian, jurist, and philosopher al-Ghazzali (d. 1111) whose major work, al-Mustazhiri written in 1095, and other shorter works, contained a detailed refutation of Nizari Ismailis. However, it was the treatise of polemicist Ibn Rizam “which had the greatest and most enduring impact on the anti-Ismaili writings of medieval Muslim authors” (Legends p 26). Although this treatise has not survived, it was referenced extensively by polemicist known by his nickname Akhu Muhsin in his treatise. His work was also utilized by later historians including al-Baghdadi (d.1037), Nizam al-Mulk (d. 1092), al-Nuwayri (d. 1332), Ibn al-Dawadari (d. 1335), among many others. Halm states that al-Maqrizi (d. 1442), a Sunni writer, “was the first historian to recognize the importance of the Fatimids in the history of Egypt and Syria… he describes the Ismaili dynasty with great respect … To him the Fatimids are not heretic…” (The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning p xiii).

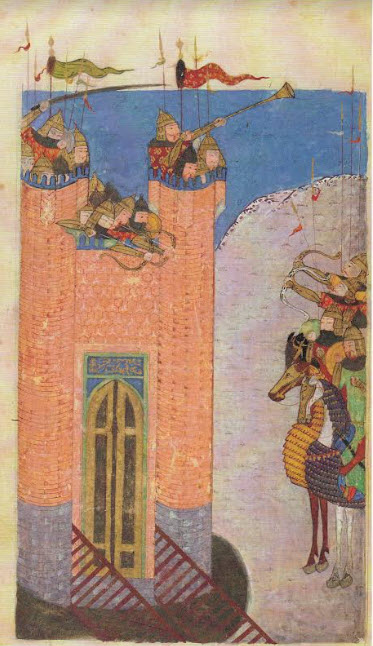

Alamut

In 1090, anticipating the end of the Nizari Ismaili Fatimid rule, Hasan Sabbah acquired the fortress of Alamut in northern Persia (modern-day Iran) for the refuge of Ismailis, marking the founding of what would become the Nizari Ismaili state of Alamut which lasted some 166 years until it was destroyed by the Mongols. Over the next 150 years, the Ismails acquired a network of over 200 fortress in Persia and Syria that were also a refuge for other communities escaping persecution.

(More about Hasan Sabbah here)

Assassination has been part of warfare since the dawn of civilisation. Among the numerous assassinations are the Egyptian pharaoh Teti of the Old Kingdom Sixth Dynasty (23rd century BCE), Phillip of Macedon in 336 BCE, Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, and so on. In Muslim history, the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs did not hesitate to order the murder of their leading critics especially if they were Shi’i (Willey, Eagle’s Nest p 61). Furthermore, whenever a prominent person was murdered, the Ismailis were blamed for it.

The term hashishiyya, meaning assassins, was increasingly applied to the Nizaris of Alamut. According to the legend, Hassan Sabbah plotted to take over the Muslim world, “and in pursuit of this dream he sent out his fanatical devotees to assassinate his enemies. Before commencing their mission, so the story goes, they were laced with hashish, served by beautiful damsels in an enchanted garden, in order to remind them of the delights awaiting them in Paradise after death” (Ibid. p xvi). This is a completely absurd since the inhibiting effects of the drug would have made it impossible for them to carry out their allegedly highly-skilled tasks. However, these legends caught the attention of the Crusaders and their chroniclers, who did not know much about Islam and even less about the Nizari Ismailis.

The Europeans believed that Muslim expansion into Spain, and their presence in the holy land, was an intrusion into Christian territory. Furthermore, Christian scholars believed that Prophet Muhammad “was the Anti-Christ and the rise of Islam heralded the imminent end of the world.” Thus the Crusades aimed to re-claim Christian lands from a people they had identified as enemies (Daftary, The Assassin Legends p. 51).

By the final decades of the twelfth century, the Crusaders and their occidental observers had already begun to add their imaginative aspects to these tales.

The earliest known European account claiming to explain the behavior of the Nizaris was by Burchard of Strassburg who had been sent on a diplomatic mission to Syria in 1175 by Frederick I Barbosa. In his report Burchard wrote about the distorted beliefs and practices of the Nizaris. By the late 1170s, this report was utilised by others in northern Europe.

“Like other medieval Europeans with some limited and distorted knowledge of Islam, Burchard may also have been familiar with the ideas, then current in certain Christian circles, about the ‘sensual’ nature of paradise promised to the Muslims. The Latin translation of the Quran, produced in 1143, had already introduced paradise to mediaeval Europe, and Pedro de Alfonso and others after him had dwelled polemically on the hedonistic delights of the Islamic ‘garden of paradise’ to prove that Islam was not a spiritual religion, and, therefore, not comparable to Christianity. In time, the European conceptions of the Islamic paradise, rooted in the Quranic descriptions, were incorporated into the Assassin legends, culminating in Marco Polo’s detailed account of the Nizari ‘garden of paradise’ (Ibid. p100).

None of the variants of the Assassin legends can be found in non-polemic Muslim sources produced during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the formative period of the legends in Europe. Mirza states “even Juwayni, the ardent anti-Ismaili, does not narrate any activities of illegality or unrestricted license” (Syrian Ismailism p31).

The Crusaders had no contact with the Persian Nizaris and consequently did not produce imaginative tales about them. It was only starting with Marco Polo ‘s accounts that the Assassin legends began to be extended to the parent Nizari community…” (Daftary, Assassin Legends p 93).

In 1256, Alamut collapsed under the onslaught of the Mongols, and in the early 1270s, the Syrian fortresses surrendered to the Mamluks, who also successfully reduced the territories of the Crusaders. Subsequently the Nizaris lived discreetly in order to escape persecution. Under such circumstances, the Europeans had less reason to write about them. Westerners remained unaware of their existence until the early nineteenth century, when the Nizaris were re-discovered in Syria.

Sources:

Farhad Daftary, A Short History of the Ismailis, Edinburgh University Press, 1998

Farhad Daftray, Assassin Legends: Myths of the Isma’ilis, I.B. Tauris, London, 1994

Nadia Eboo Jamal, Surviving the Mongols: Nizari Quhistani and the Continuity of the Ismaili Tradition in Persia, I.B Tauris, New York, 2002

Nasseh Ahmed Mirza, Syrian Ismailism: The Ever Living Line of Imamate, Curzon Press, 1997

Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, I.B. Tauris, London, 2005

Contributed by Nimira Dewji, who also has her own blog – Nimirasblog – where she writes short articles on Ismaili history and Muslim civilisations.

I will give this Article to my children

LikeLike