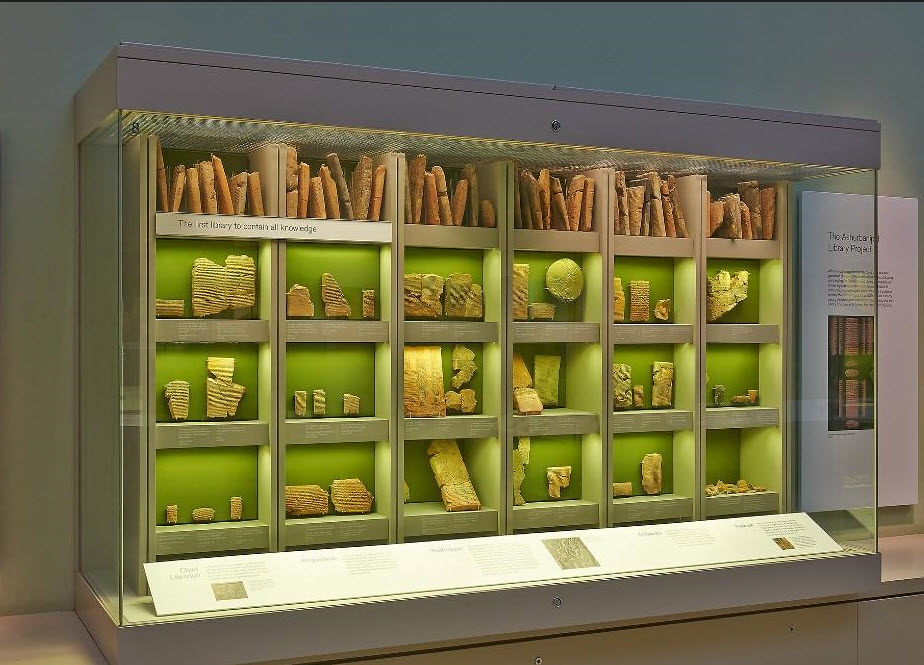

Derived from the Latin liber, meaning book, libraries, as rooms or buildings storing collections of written materials have existed for a long time, dating back to at least the third millennium BCE Babylonian times. Excavations have discovered Assyrian tablets in Egypt dating to the second millennium BCE. King Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BC) had an archive of 25,000 tablets collected from throughout his kingdom; some of his collection is housed at the British Museum.

Ancient China also maintained works of antiquity including texts on medicine, poetry and prose, works of Confucius (551-479 BCE), and military records.

The earliest institutional library in Athens was founded in the fourth century BCE by the various schools of philosophy. Aristotle’s library, founded to facilitate scientific research, formed the basis for the library at Alexandria in Egypt, which became prominent during antiquity. The founders of this library, it is believed, aimed to collect the best copies of the entire collection of Greek literature and arrange them systematically. However, the library was destroyed in a fire around 48 BCE. The current Bibliotheca Alexandrina, opened on October 16, 2002, was built to commemorate the ancient library. It was recipient of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2004.

In ancient Rome, it was fashionable to own a library – excavations have revealed what would have been library rooms in private residences (See Library was a symbol of the cultivated sovereign).

The Nalanda Mahavihara in Bihar, north-eastern India, home to one of the most lauded intellectual centres of the ancient world, dating from the 3rd century BCE to the 13th century CE. Its library is said to have housed the world’s largest collection of Buddhist literature. The ruins at Nalanda are a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In the Islamic world, book collections were initially linked to religious collections – in mosques and madrasahs (theological schools); some mosques had separate rooms for non-religious materials which were often donated by scholars. Motivated by the central message of the Qur’an to pursue knowledge and the Prophetic Tradition, ‘Seek knowledge, even though it comes from China,’ the rulers incorporated some of this material into their own way of looking at the world, founding many institutions of learning; faith and learning were seen to be interactive and not in conflict with each other. This began the period of translation compilation, and advancement, ushering in the era of knowledge exchange whose effects are felt today (Nanji, The Muslim Almanac p 5).

Large collections of books were also housed in palaces and in the homes of the wealthy. When the Muslims learned the art of paper-making from the Chinese, it enabled them to reproduce the written word cheaply.

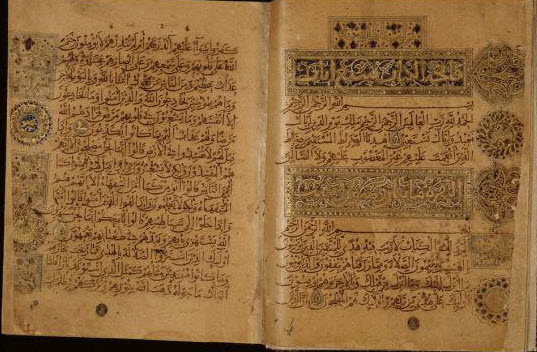

Learned people were book collectors, but also produced tomes as authors and copyists. “The typical mechanisms by which books were purchased, owned, and gathered in collections consisted of copying them, presenting them as pious donations, and trading in them. Also, since books were generally very expensive, they were considered valuable commodities to be passed on through inheritance as family heirlooms” (Cortese, Intellectual Interactions in the Islamic World p 408-409).

Fatimids

Named after the Prophet’s daughter, the Fatimids established their rule in 909 in Tunisia, in North Africa. During their reigns, Imams al-Mahdi and al-Mansur founded the cities of al-Mahdiyya and al-Mansuriyya, named after them respectively. In 973, Imam Al-Mu’izz transferred the dynasty’s capital to a new city in Egypt that he designed.

Imam al-Mu’izz founded Al-Azhar mosque in 973 CE, named in memory of the title al-Zahra (‘the luminous’), which is associated with Fatima, the daughter of the Prophet and the wife of the first Shi‘a Imam, Hazrat Ali, from whom the Fatimids claimed direct descent.

In 988, the Al-Azhar mosque became a university, subsequently developing into a major seat of learning with lecture halls and residences richly endowed to support students and teachers. Al-Azhar became the foremost Fatimid institution of higher learning, with sessions on Qur’anic studies, theology, and law. Admission was open to everyone including women. The culture of unhindered scientific thought attracted the finest scholars and artisans of the age to the Fatimid court, regardless of their religious persuasions.

In addition to the Al-Azhar, the Fatimid Caliph-Imam al-Hakim established Dar al-Ilm (House of Wisdom) 1005 in the palace. These institutions of learning had the caliphs’ personal collections of books, but the palaces also contained libraries and reading rooms that served as meeting places for scholars, astronomers, doctors, jurists, and mathematicians. According to a catalog prepared in 1045, the library at Dar al-Ilm contained 6,500 volumes on various subjects.* The Fatimid libraries were subsequently looted and many manuscripts and books were either destroyed or scattered all over the world by scholars, merchants, and collectors.

Manuscripts dating to the tenth and eleventh centuries that have been preserved by curators or in private collections today could have been from the Fatimid royal libraries or produced in Egypt during Fatimid rule. Sources suggest that a manuscript produced by a prominent calligrapher of the time, Ibn al-Bawwab in 1000-1, housed in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin could have once been in the Fatimid library.

Book Production

The warraq was the person associated with medieval Islamic book production. “Encompassing the role of paper vendor, seller of writing tools, copyist and scholar in his own right at any one time, the warraq could occupy varied positions on the social scale from a marginal who scraped a living through writing for others to a distinguished member of the scholarly elite. … Whether produced for a commission or through individual initiative, the ultimate purpose of copying books as a profession was to sell them. For this reason often the activities of the copyist overlapped with that of the kutibi, the vendor or broker of volumes already in circulation” (Cortese, Intellectual Interactions in the Islamic World p 409).

In terms of cultural impact, by circulating extant books, the kutubi provided greater potential for popularization of a broader, random and diverse range of subjects to a broader audience while, at the same time, contributing – deliberately or by default – to the life or death of a particular form of literary tradition” ( Cortese, Intellectual Interactions in the Islamic World p 409).

“Fatimid Egypt offers a distinctive social, religious and cultural context in which to map the function and role that the book trade played in facilitating intellectual interaction. While defined by activities and events linked to and/or determined by an Ismaili dynasty – except for strictly da’wa literature – the practical means of book exchange transcended Ismailism as a doctrinal entity…. The Fatimids, as a Shi’i Ismaili dynasty were a religious minority ruling over a majority Sunni population, a state of affairs that meant that contrasting and competing scholarly traditions were brought into contact. For example, the imam-caliph al-Hakim, founded in Cairo, his ‘Abode of Knowledge’ or dar al-ilm ostensibly as an outreach venture intended to serve scholars irrespective of their religious affiliations. In Egypt the Fatimids became the first Muslim dynasty to give their patronage to major libraries located in royal palaces and in the learning institutions they supported” (Cortese, Intellectual Interactions in the Islamic World p 411). The Fatimid library was a wonder of the medieval world (Halm, The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning p 91). The Fatimids “recognized the universality of knowledge and opened the door of knowledge to all people” (Akman).

“Books were produced for Ismaili da’wa purposes with a very strictly limited circulation; however, books were written on Ismaili law that could be publicly circulated and, outside the doctrinal context, books on all the known fields of learning were written, copied, circulated, and praised. The book culture that the Fatimids promoted was so infectious that it was embraced by high-ranking officers of state – for example the vizier Ibn Killis [d. 991] and al-Afdal [d. 1121] – as well as the wider urban culture” (Cortese, Intellectual Interactions in the Islamic World p 411).

Although the price of books varied from one region to another due to fluctuations in currency values, “it is generally agreed that books were an expensive commodity. Typically, written sale contracts were drafted when books were purchased, a practice that otherwise was only applied to the purchase of houses, other immobile property, and slaves. With so much at stake, book acquisition would need careful consideration and discernment on the part of the buyer.

Ibn Jama’a [d. 1333] in his Tadhkira provides guidelines on how to buy a book. For example, to ensure its quality the buyer should check that it is complete at beginning and end; that there are no missing parts in the middle; that the general state and quality of the paper is consistent with the asking price. The book’s editorial qualities would have to certain expectations and conventions. Indeed we can detect a degree of preciousness over the quality of books at the Fatimid court… In fact, it appears that the purchase of existing books was not contemplated in the detailed budget of al-Hakim’s dar al-ilm where, instead, enormous sums were set aside for paper, scribes, writing tools and book restauration” (Cortese, Intellectual Interactions in the Islamic World p 411-412).

“In times of cash-flow crisis books also entered the book market through being institutionally and formally released from the Fatimid royal libraries to serve as collateral in lieu of monetary payments owed by the regime to government officials… books served as financial security…” (Cortese, Intellectual Interactions in the Islamic World p 418).

“For all its triumphs and upheavals, it was ultimately the cultural, religious and economic fluidity that characterised Egypt under the Fatimids that transformed that region from a cultural backwater into a centre of intellectual activity serving as a launch pad for books to boldly go where no volumes have gone before” (Cortese, Intellectual Interactions in the Islamic World p 426).

Sources:

*Jonathan M. Bloom, Arts of the City Victorious, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007

Library, Encyclopaedia Britannica

Azim Nanji, “The Prophet, the Revelation, and the Founding of Islam,” The Muslim Almanac, Gale Research Inc., Detroit, 1996

Delia Cortese, “Beyond Space and Time: The Itinerant Life of Books in the Fatimid Market Place,” in Intellectual Interactions in the Islamic World, Edited by Orkhan Mir-Kasimov, I.B. Tauris, London, 2020

Heinz Halm, The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning, I.B Tauris, London, 1997

Nakhlu Zatul Akmam, Fatimid Library: History, Development and Management, Researchgate