“I gaze upon forms with my optic eye,

Because the traces of spiritual meaning are to be found in forms.

This is the world of forms, and we reside in forms,

The spiritual meaning cannot but be seen in forms.”

Awhad al-Dīn Kirmānī, Heart’s Witness, Tehran: Imperial Iranian Academy of Philosophy,

1978

The term Islamic art refers to visual arts produced in Islamic regions by a variety of artists and for diverse consumers, not necessarily by Muslims and for Muslims. The term does not refer to a particular style or period, but covers a broad scope, encompassing the arts produced in the traditional heartland of Islam (from Spain to India) for fourteen-hundred years.

Titus Burckhardt states that “the art of Islam is essentially a contemplative art, which aims to express above all, an encounter with the Divine Presence.”1 Islamic art then, is the external expression of inner spirituality. Verses of the Qur’an are engraved or embossed on buildings such as the masjid, madrasa, and shrines of Sufi saints as well as on everyday objects such as household utensils, cloth, wood, inspiring the remembrance and contemplation of God.

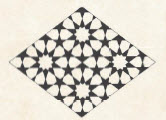

Islamic art first and foremost reflects the concept of tawhid, Divine Unity through a variety of forms such as the circle, the basis of complex geometrical patterns. Because a circle has no beginning or end, it is never-ending, thus reminding that God is infinite.

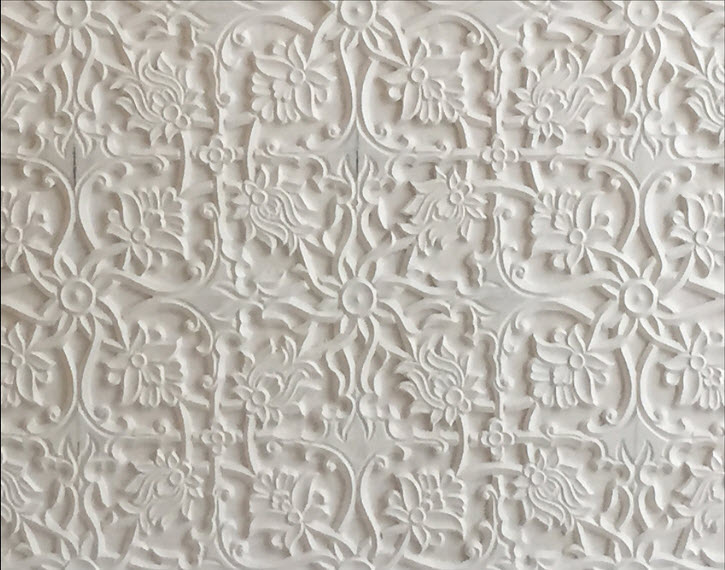

Complex geometric patterns and interlacing create the impression of un-ending repetition also adding to the concept of God’s infinity. The repeating patterns also demonstrate that “in the small, you can find the infinite.”2

The orderliness of the geometric patterns convey an aura of spirituality and a sense of transcendent beauty. The a-centric arrangements were used in order to avoid focal points, resonating with the view that the Absolute is not centred “in a divine manifestation but whose presence is an even and persuasive force throughout Creation.”2

Interlacing, based on Roman styles, developed into a highly specialised art form, inviting the eye to follow it, and transforming vision into a rhythmic experience. The shapes of the interlacing are built up from one or several regular figures inscribed in a circle which are then developed further into star-shaped polygons, forming a continuous network of lines radiating from one or several centres.

Arabesque, a frequently used ornamentation style, is characterised by its rhythmic waves, often implying an infinite design with no beginning or end. One of the contributing factors to the infinite pattern of the arabesque is the growth of leaves, flowers or other motifs from one another rather than from a single stem. Perhaps the vegetation evoked themes of Paradise, described in the Qur’an as a garden. Often combined with interlacing geometric and other decorative patterns, arabesque represents a visual form of the laws of rhythm.

Light is the most common symbol across all religious traditions signifying the Divine. There are numerous verses in the Qur’an that use the metaphor of light (nur). In the Shia interpretation, these verses are linked to the principle of Imamat.

Seyyed Hossein Nasr states that “to grasp fully the significance of Islamic art is to become aware that it is an aspect of the Islamic revelation, a casting of the Divine Realities (haqa’iq) upon the plane of material manifestation in order to carry man upon the wings of its liberating beauty to his original abode of Divine Proximity.”2

Sources:

1Titus Burckhardt, Art of Islam, Language & Meaning (accessed March 2017)

2Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Religious Art, Traditional Art, Sacred Art (accessed March 2017)

3Jonathan Bloom, Arts of the City Victorious, Yale University Press in association with The Institute of Ismailis Studies, 2007.

Sheila Blair, Islamic Art (accessed March 2017)

Marina Alin, “Unity in Diversity– Reflections on Styles in Islamic Art,” Islamic Art & Architecture (accessed March 2017)

Compiled by Nimira Dewji

Previously on Ismailimail…