The fundamental reason for the pre-eminence of Islamic civilisations lay neither in accidents of history nor in acts of war, but rather in their ability to discover new knowledge, to make it their own, and to build constructively upon it. They became the Knowledge Societies of their time.”

Mawlana Shah Karim, AKU Convocation, 6 December 2006

The Berber governor of Ifriqiya (modern-day Tunisia, western Libya, and eastern Algeria) tasked his general Tariq ibn Ziyad to conquer the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day southern Spain, Portugal, Andorra, Gibraltar, and a small part of France).

From the Greek barbar meaning “someone who speaks in a foreign language,” and in Latin barbaria, the language of the Romans, meaning “foreign lands,” the term subsequently became “Berber” and was referred to peoples living in North Africa.

In the year 711, Tariq crossed the straits which were to be forever identified with him: Gibraltar is from the Arabic jebel al-Tariq – ‘the rock of Tariq.’ The areas that came under Muslim rule came to be known as al-Andalus (711-1492).

Abd al-Rahman I (r.756-788), of the Umayyad family that ruled in Damascus, established himself as governor in southern Spain, making Cordoba, an old Roman town, his capital. He commissioned the building of a palace as well as the Great Mosque that was a synthesis of the local as well as the Byzantine styles, and became a wonder of the Middle Ages.

Abd al-Rahman strengthened agriculture through accurate land surveying, efficient irrigation canals, and proficient technical expertise which established the region’s prosperity for his successors. By the tenth century, Cordoba, and later Seville and Toledo, became renowned intellectual and cultural centres, attracting numerous scholars.

Under the reign of Abd al-Rahman III (r.912-961), al-Andalus grew into an empire with a diverse religious and ethnic population. He founded the palace city of Madinat al-Zahra (the city of Zahra), named after his wife. Once an important cultural centre, the grand city was destroyed during a civil war of 1010-1013. The museum, completed in 2008 near the archaeological site of the former palace city, was awarded the Aga Khan Award of Architecture in 2010. The Jury citation stated:

“The Madinat al-Zahra museum is a symbol of the convivencia evoked by the name Andalusia and bears testimony that indeed, Cordoba is the future, not only the past.”

By 1055, al-Andalus, once known as the jewel of the Islamic land, was weakened and broke into several independent territories, including the kingdom of Portugal, which were ruled by various dynasties including the North African Almoravids (1056-1147), who had founded Marrakesh in Morocco as their capital, and the Almohads (1130-1269). By the end of Almohad rule, Muslims lost control of al-Andalus except for Granada. The rulers of the Emirate of Granada had signed a special agreement with the Kingdom of Castile, one of the most powerful Christian kingdoms, to become a tributary state of Castile. However, in 1492, Granada was conquered, ending seven centuries of Muslim rule.

Along with the Great Mosque, the Casa Zafra (Zafra House) built in the fourteenth century during the time of the Nasrid dynasty, and the Alhambra, considered the hallmark of Islamic architecture, are some of the greatest monuments of al-Andalus.

The Alhambra is on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. In 1998, the seventh awards of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture were presented at the Alhambra Palace.

The most enduring legacy of Muslim Spain, or Andalusia (Andalucia), ruled by Muslims for seven centuries was the creation of a Knowledge Society that contributed to its scientific breakthroughs and academic marvels.

Intellectual and cultural pursuits

At various times, Andalusia enjoyed a healthy economy, stable rule, peaceful living conditions, and wealthy rulers supporting intellectual and artistic traditions resulting in cultural, artistic, and scholarly achievements. The legacy of Andalusia is reflected in the philosophical, theological, and legal writings which influenced subsequent scholarship in Europe.

Don Raimundo, Archbishop of Toledo from 1126 to 1151, was convinced of the importance of the Arab philosophers for an understanding of Aristotle, and decided to make their works available in Latin. He established the first school of translation from Arabic into Latin in the city. Much of the Greek philosophical tradition was, for a long time, known primarily through the Latin translations of the Arabic texts. The impact of the Spanish Islamic philosophers, especially Ibn Rushd, on the Catholic theologian Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274) is widely acknowledged.

Also translated into Latin at the Toledo school were works of Ibn al-Haytham, known as father of optics and who laid the foundation for today’s laser technology; al-Farabi, credited with preserving the works of Aristotle; al-Khwarizmi whose famous book title lives on in the terms algorithm and algebra; and many others. Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine, first translated into Latin in the twelfth century in Andalusia, quickly became the standard medical text in Europe.

This astrolabe, which may have been made in Toledo, has inscriptions bearing the names of constellations in both Arabic and Latin. Later, Hebrew was added to one of the plates (Aga Khan Museum).

Invented by the Greeks in about the second or third century BCE, the astrolabe was further advanced by the Arabs in the eighth to eleventh centuries, and introduced to Europe through North Africa and al-Andalus as early as the eleventh century. It seems likely that the use of Arabic star names in Europe was influenced by the importing of these instruments.

The patterns and structures of learning, of the organisation of institutions, and of professional development were transmitted from the Mediterranean Islamic region to western Europe. It is suggested that the earliest universities in Europe, such as Bologna, Paris, and Oxford, were founded on Islamic models.

Thomas Burman notes that “al-Andalus – especially its great cities of Cordoba and Seville – eventually became the center of a great civilization.” He adds that “the study of pure philosophy, which had been only a minor pursuit in the earlier period, reached a level of considerable prominence…when thinkers such as Ibn Tufayl (d.1185) and Ibn Rushd (d. 1198) wrote some of the greatest philosophical works in Islamic history.” (The Muslim Almanac, p 111).

After al-Andalus was no more, its culture lived on in various ways including architecture whereby the hybrid styles became the standard in later medieval Spain. The literature, especially Romance dialects of Spain, borrowed numerous Arabic words. For example, Burman notes that when uttering a wish, “such a statement begins with the word ‘Ojala,’ which is merely the Castilian corruption of the familiar phrase…In shaa Allah…” (The Muslim Almanac, p 113).

Some foremost Andalusi intellectuals who contributed to knowledge societies

Abu’l Hasan Ali ibn Nafi (d. 857) came to Cordoba from Baghdad, was given the name Ziryab, meaning blackbird due to his beautiful singing voice. He was a poet, singer, composer, and teacher, and was also learned in geography, astronomy, and history. He founded a school of music in Cordoba training singers and musicians.

Al-Battani (d. 929) was a critic of Ptolemy, whose work contributed to solving the puzzle of the heavens, and whose work was used for centuries. He calculated astronomical charts on the movement of celestial bodies, and helped to develop the branch of mathematics called trigonometry, which he used, in turn, to calculate accurate solar and lunar timekeeping.

Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (d. 1013), known in the West as Abulcasis, was court physician to the caliph al-Hakam II (r.796-822) and is believed to have introduced new medical procedures such as replacing lost teeth with bone, and using plaster casts for setting broken bones. He wrote numerous works including a medical encyclopaedia which included symptoms of 325 illnesses and their treatments; 200 designs for surgical instruments, and descriptions of medical procedures. This work was later translated into Latin and published in Europe in the 15th century.

Ibn Zuhr (d. 1162) was known as Avenzoar; his works had a lasting impact on medicine in Europe. His text Taysīr fī al-mudāwāt wa al-tadbīr (“Practical Manual of Treatments and Diet”), later translated into Hebrew and Latin, described inflammation of the membranous sac surrounding the heart, and outlined surgical procedures for tracheotomy, excision of cataracts, and removal of kidney stones.

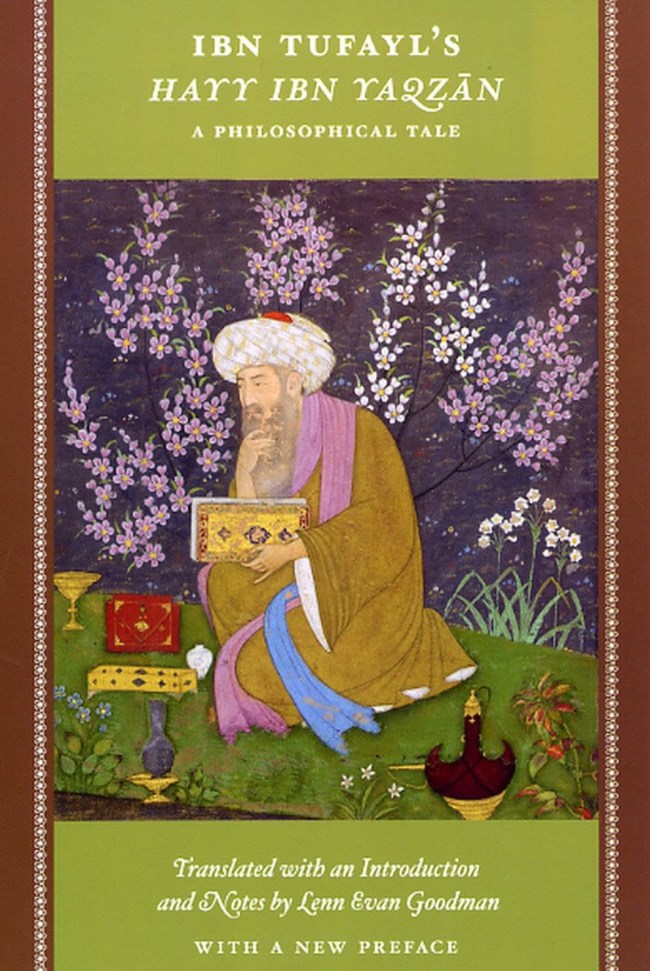

Ibn Tufayl (d. 1185) was physician to the Almohad ruler Abu Ya‘qub Yusuf (r.1163-1184) and the author of the philosophical tale Hayy ibn Yaqzan (Living, Son of Awake), which is thought to be the model for Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe.

Ibn Rushd (d. 1198), a philosopher, jurist, mathematician, physician, and astronomer, he became chief judge of Seville.

Known in the West as Averroes, he made his most important contributions in his commentaries on Aristotle, which were translated into Latin and had a lasting influence in medieval Europe earning him the title of “The Commentator” par excellence. He also examined the relationship between reason and religion.

Maimonides (d. 1204) a philosopher, jurist, and physician, and the foremost Jewish intellectual of the Middle Ages, wrote his most influential philosophical works in Judeo-Arabic, that is, Arabic written in Hebrew letters, which was a common practice at the time.

Muhyi al-din Ibn al-Arabi (d.1240) travelled in search of spiritual masters in al-Andalus and then to North Africa eventually settling in Damascus in 1223 where he taught and wrote numerous works of poetry, Qura’anic interpretation, law, and mysticism. He was supported by the local rulers who admired his scholarly learning.

The cities of Toledo and Cordoba have been declared by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites for their extensive cultural, intellectual, and monumental heritage.

The Andalusi period was legendary – from its literary and scientific tradition to its art, architecture, and farming techniques; their production of inlaid woodwork, polychrome tiles, and lustre-decorated ceramics remained in demand among the elite in Europe long after the end of al-Andalus. The legacy of this civilisation lives on in the architectural wonders that they left.

“Muslim scholars reached pinnacles of achievement in astronomy, geography, physics, philosophy, mathematics and medicine. It is no exaggeration to say that the original Christian Universities of the Latin West, at Paris, Bologna and Oxford, indeed the whole European Renaissance, received a vital influx of new knowledge from the Islamic world: an influx from which later Western Colleges and Universities were to benefit in turn, including those of North America.

Along with this civilisation came a magnificent flowering of the arts and architecture: the buildings created by the great Islamic Empires rank among the finest monuments of civilisation in any part of the globe.”

Mawlana Shah Karim Aga Khan IV

University of Virginia, USA, 13 April 1984

Speech

Contributed by Nimira Dewji, who also has her own blog – Nimirasblog – where she writes short articles on Ismaili history and Muslim civilisations.

Sources:

Alnoor Dhanani, “Muslim Philosophy and the Sciences,” The Muslim Almanac Edited by Azim A. Nanji, Gale Research Inc., Detroit, 1996

Thomas Burman, “Islam in Spain and Western Europe,” The Muslim Almanac Edited by Azim A. Nanji, Gale Research Inc., Detroit, 1996

Andalusia, Encyclopaedia Britannica

Religions, Muslim Spain, BBC

The History of Court of Lions