Indeed in the creation of the heavens and the earth, and in the alternation of night and day, are signs for people of understanding…(Qur’an 3:190)

And He is the One Who created the day and the night, the sun and the moon—each travelling in an orbit (Qur’an 21:33)

The central message of the Qur’an and Prophetic Tradition to seek knowledge led to the translations of works of ancient civilisations and the founding of institutions of learning. The acquisition of knowledge came to be perceived as a way of improving understanding of the faith. Early Muslim intellectuals searched for knowledge in every domain especially when the Qur’an “explicitly commands the study of the universe and the self as a means to know God….universe and the human self are viewed as inseparably linked” (The Muslim Intellectual Heritage p 108, 111).

The primary focus was on the nature of things, “describing and explaining the three fundamental domains…God, the universe, and the human soul” (Ibid. p 8). The need to make the works of previous civilisations available more widely led to a translation and compilation movement whereby Greek, Persian, Indian, Chinese, and Byzantium materials were translated into Arabic beginning around 800 CE, and advanced, and whose effects are felt today.

Rulers established translation centres, observatories, libraries, and education centres. Most patrons employed scientists as astrologers or physicians. Dhanani states “the interconnectedness of disciplines was such that an astrologer, for example, needed to know astronomy, and could not know astronomy without being versed in mathematics and natural philosophy, which, in turn, required familiarity with the cosmology of Islamic Hellenistic philosophy. With the passage of time, a new scientific role arose, that of the mosque timekeeper who was responsible for calculating prayer times as well as determining the start of the months of the Islamic lunar calendar (The Muslim Almanac p 110). From the ninth to the fifteenth centuries, scientists working in the Arabic language dominated worldwide scientific endeavor and provided the raw material for Europe’s intellectual renaissance. Astronomy was one of the greatest of these pursuits.

“The math required for astronomy was also advanced in large part by Islamic scholars. They developed spherical trigonometry and algebra, two forms of math fundamental to precise calculations of the stars” (Stirone). A few of the numerous astronomers and mathematicians include the following:

Al-Farghani (d. after 861), known in the west as Alfraganus, wrote Elements of Astronomy on the Celestial Motions around 833. This textbook provided revised values from previous Islamic astronomers. The work circulated widely throughout the Islamic world and was translated into Latin in the twelfth century, becoming the primary resource that European scholars used to study Ptolemaic astronomy until the seventeenth century.

Al-Battani (d. ca. 929), known by a Latinised names Albategnius, Albategni or Albatenius, composed work on astronomy, with tables, containing his own observations of the Sun and Moon, and a more accurate description of their motions than that given in Ptolemy’s Almagest. He compiled a catalogue of 489 stars, refined the existing values for the length of the year, (which he gave as 365 days 5 hours 46 minutes 24 seconds) and of the seasons, also documenting a few eclipses that he witnessed. His work had a large influence on scientists such as Tycho Brahe, Kepler, Galileo, and Copernicus (Famous Scientists). A lunar crater is also named after Al-Battani.

Al-Sufi (d. 986) was a Persian astronomer and mathematician known in the West as Azophi. In 903, he published the first-ever critical revision of Ptolemy’s star catalogue, correcting erroneous observations and adding others not recorded by the Greek master astronomer. Al-Sufi’s treatise on star cartography, or uranography, compiled in 964, was called The Book of Constellations of the Fixed Stars (Kitab Suwar al-Kawakib al-Thabita) and became a classic of Islamic astronomy. “Most of the names that we use today came to us from al-Sufi’s list, either via the European–Mediterranean civilization of the Greeks or through the Arab–Islamic civilisation” (Lebling).

Al-Sufi also contributed to the building of an important observatory in the city of Shiraz as well as constructing many astronomical instruments such as astrolabes and celestial globes. His influence reverberated throughout history reaching as far as the end of the 19th century” (Hafez, Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi and his book of the fixed stars: a journey of re-discovery). A lunar crater is named Azophi, in recognition of his contribution to astronomy.

Ibn Yunus (d. 1009) from Egypt found faults in Ptolemy’s calculations about the movements of the planets and their eccentricities. He served two Caliphs of the Fatimid Caliph Imams al-Aziz and al-Hakim, making astronomical observations for them between 977 and 1003. To al-Hakim, he dedicated his major work al-Zij al-Hakimi al-kabir (a zij is an astronomical handbook with tables) in which he cites some thirty solar and lunar eclipses witnessed between 829 and 1004. Ibn Yunus’s influence, in the form of his methodology and parameters, as well as actual observations, can be seen in many later Islamic tables, such as al-Tusi’s Ilkhani zij 250 years later, where Ibn Yunus’s values for the longitudes of the sun and moon are used (University of Cambridge). A lunar crater is named after Ibn Yunus for his contribution to the field of astronomy.

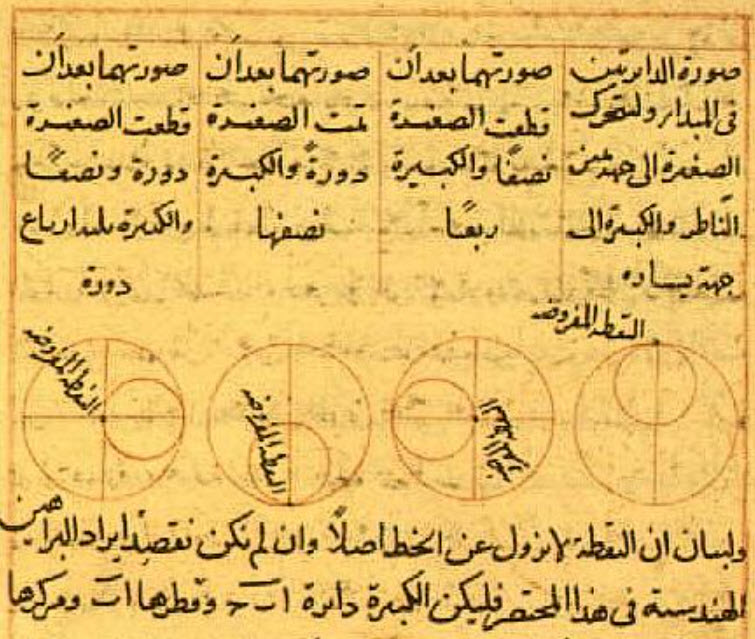

The main goal of astronomers was to develop models involving uniform motions around the centre of the universe—the Earth—that were compatible with observations. Among the discrepancies in Ptolemy’s works was that it did not satisfy both observational and physical principles. While many brilliant minds such as al-Haytham, Ibn Rushd, Ibn Bajja, and others, were occupied with this dilemma, it was Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (d.1274) who developed a revolutionary solution, what is known as the Tusi Couple that converts angular motion to reciprocating linear motion, which is believed to have influenced Copernicus’s work (Rabin, Sheila, Nicolaus Copernicus, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

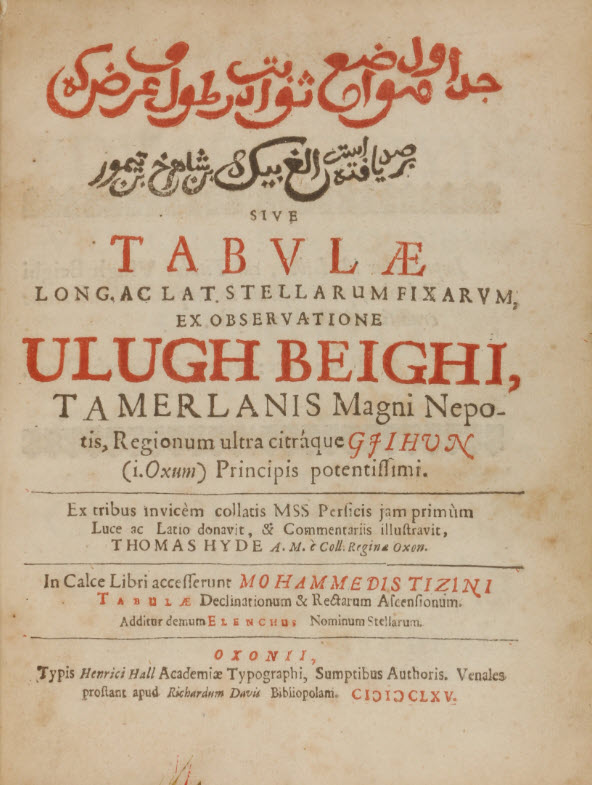

Ulugh Beg, who made some of the best astronomical observations of his time, is mostly remembered as a patron of mathematics and astronomy. In 1417, he established a madrasa, a religious school or college, in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, where mathematics and astronomy were among the most important subjects taught. In 1420 he established his own observatory on a rocky hill outside the city of Samarkand. The main instrument in this observatory was a huge sextant called the Fakhri sextant. The radius was 40.04 meters, which made it the largest astronomical instrument in the world of that type, making its graduation very accurate. Ulugh Beg worked nearly two centuries prior to the invention of the telescope. His work eventually became known in Europe, with the publication of his works in London in 1650 in Latin, and later the first of many European editions of his star tables. He was one of the earliest to advocate and build permanently mounted astronomical instruments (Mary Hughes, Ulugh Beg, Perth Observatory).

In 1665, English orientalist Thomas Hyde published the first-ever translation of Ulugh Beg’s star tables for European readers, with an extensive commentary on the star names. This Latin work, published at Oxford, bore the scholarly title Tabulae longitudinis et latitudinis stellarum fixarum ex observatione Ulugh Beighi (Lebling). A lunar crater is named after Ulugh Beg.

Among the various ancient tools to study the heavens, the astrolabe is one of the most sophisticated scientific instrument ever made. From the Greek astro meaning ‘star,’ and labe meaning ‘finder,’ it was invented by the Greeks in about the second or third century BCE and advanced by scientists and scholars in the medieval Islamic regions in the eighth to eleventh centuries CE. It was introduced to Europe through North Africa and al-Andalus as early as the eleventh century. It seems likely that the use of Arabic star names in Europe was influenced by the importing of these instruments.

A prominent, skillful builder of astrolabes, Maryam Al-Ijliya, also known as Maryam Al-Astrulabi, was born in the tenth century in Aleppo, Syria. Mariam’s interest in developing astrolabes grew when she saw her father, known as Al-Ijliyy al-Asturlabi, building them, having apprenticed with an astrolabe maker in Baghdad. Her masterful skill of making astrolabes impressed the ruler of the Emirate of Aleppo, Sayf al-Dawla [r. 944 to 967 CE], who employed her in his court (Aga Khan Museum). Mariam’s significant contributions in the field of astronomy were recognised when the main-belt asteroid 7060 Al-‘Ijliya, discovered by Henry E. Holt at Palomar Observatory (San Diego, USA) in 1990, was named after her.

Islamic civilisations have played a critical historical role in advancing astronomy and the understanding of the heavens. Islamic scholars recorded a number of eclipses according to the lunar calendar. Professor Jamil Ragep states “There is virtually no controversy, at least among reputable scholars, that Islamic astronomy influenced medieval and early modern astronomy through the Latin translations or reworkings of numerous Islamic astronomical works and through the Arabic translations of Greek astronomical texts” (Science and Thought Series, No: 37, p ix).

Sources:

Alnoor Dhanani, “Muslim Philosophy and the Sciences,” The Muslim Almanac Ed. Azim A. Nanji, Gale Research, Detroit

Jamil Ragep, Islamic Astronomy and Copernicus, Turkish Academy of Sciences Publications Science and Thought Series, No: 37 (PDF)

Laura Poppick, The Story of the Astrolabe, the Original Smartphone, Smithsonian Magazine

The Star Catalogue of Ulugh Beg

Robert W. Lebling, Arabic in the Sky, Aramco World

S.S Said and F.R. Stephenson, University of Durham, Solar and Lunar Eclipse Measurements by Medieval Muslim Astronomers, SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System

Shannon Stirone, How Islamic scholarship birthed modern astronomy, Astronomy.com

William C. Chittick, The Muslim Intellectual Heritage And Its Perception In Europe

Contributed by Nimira Dewji, who also has her own blog – Nimirasblog – where she writes short articles on Ismaili history and Muslim civilisations.