Nizari Ismaili history is divided into: Early Ismailis, Fatimid (909-1171), Alamut (1090-1256), Post-Alamut (thirteenth to fifteenth centuries), Anjundan Revival (fifteenth to eighteenth centuries), and Modern Period (beginning in the nineteenth century).

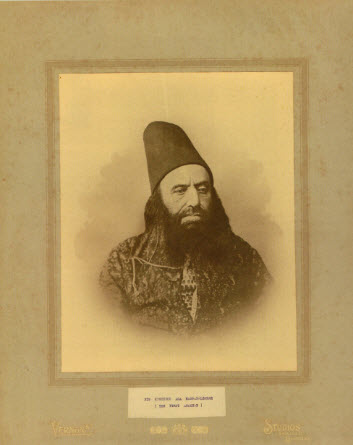

The modern period of Nizari Ismaili history began when Imam Imam Hasan Ali Shah migrated to Bombay (now Mumbai) in the nineteenth century. Born in in Kahak (in modern-day Iran) in 1804, Imam Hasan Aly Shah succeeded to the Imamat at the age of thirteen after the murder of his father.

In his autobiography, the Ibrat-afza, witten following his departure from Persia and settlement in India, Imam states:

“…I was at the age of seven when my martyred father was taken to Yazd and Imani Khan Farahani [Imam’s brother-in-law and husband to his sister Shah Bibi] was deputised to oversee some villages belonging to us. These villages were given to us by the late Agha Muhammad Khan [Qajar r.1789-1797 (founder of the Qajar dynasty)] in exchange for some properties in Kirman at the time when my father and my relatives were moved from Kirman. There was a certain Muhammad Ali who was the chief of the village of Rivkan of Mahallat [The Aga Khan’s ancestors had lived in the nearby village of Kahak since the late 11th/17th century and held a large number of properties in the area and in surrounding regions (Memoirs p79 n, 140)]. He did not submit to Imani Khan’s directive. Therefore, in order to get some peace of mind, he wrote a letter to my late mother making solemn promises and vows. When my late mother felt confident that nothing would happen to him, she sent him to Farahan, but Imani broke his vows and imprisoned him … My mother went to Farahan [a city in the province of Markazi] in order to vouch for him and intercede on his behalf but Imani Khan left Mashkabad, which was his residence, for another village and hid himself.

Because of these things we were compelled to leave our home and residence in Mahallat and settle perforce in Qumm at the age of eight. In Qumm … life became so hard and we were so poor that we could barely obtain even yoghurt and bread. Any assistance either from relatives or strangers was entirely inconceivable until I was thirteen years old. It was in this year that my father was martyred in Yazd.

After this incident, relatives and strangers all unanimously opposed me… my late mother finally lost patience and departed for the royal capital in Tehran and sat there in the majestic royal court seeking justice … The passionate petition of my late mother touched the heart of His Majesty [Fath Ali Shah] …His Majesty … began compensating for what had been lost and rectifying all the damages we had sustained over the years and in past times… he [also] raised me up in distinction to become his son-in-law …” (Memoirs p 79-81).

Imam Hasan Aly Shah became involved in the public life of his native province. In time, Fath Ali Shah appointed him governor of the district of Qumm and bestowed upon him the honorific hereditary title of Agha Khan (Aga Khan) – a title that has remained in use by his successors to the present Imam.

In 1835, Muhammad Shah (r.1834-1848), Fath Ali Shah’s grandson and successor, appointed the Imam governor of the province of Kirman. At the time, there was much political unrest in the province and Imam brought calm to the region. However, despite his successes, he was informed that he would be replaced by one of the monarch’s brothers. When Imam refused to accept his dismissal, he was confined to the citadel of Bam along with his family and his army.

After fourteen months, when the accusations against him in the civil unrest were proven false, Imam was taken to Kirman in captivity, eventually being permitted to return to Mahallat.

End of Persian Period

Owing to further political unrest, Imam migrated to Qandahar, Afghanistan in 1841, marking the end of the Persian period in Nizari Ismaili history that had lasted some seven centuries since Alamut time. Here, he received deputations from representatives of Ismailis living in Kabul, Badakhshan, Bukhara, and Sind. The Imam began establishing more direct connections with followers in remote parts of Asia.

When Imam left Persia, the Persian Nizaris were left without leadership as the bulk of the senior leaders of the community had also migrated with the Imam. For the first time in almost seven centuries, the Persian Nizaris were deprived of direct access to the Imam and the headquarters of the da’wa. Henceforth, the Nizari communities, separated from one another by long distances, became highly disorganised each community developing autonomously on the basis of its own resources and local initiatives. Deprived of the guidance and protection of the Imam, the scattered Nizari communities were now subjected to periodical persecution.

A few years after his migration, according to oral traditions of the Persian Nizaris, Aga Khan I appointed Mirza Hasan, who was residing in the village of Sidih and whose family had served the Imams, to manage the affairs of the community in Persia, a position he held for forty years. Mirza died around 1887-1888; he was succeeded by his son Murad Mirza, “who had his own rebellious ideas regarding the affairs of the Persian Nizaris” (Daftary, The Ismailis Their history and doctrines p 535). As the community had lost direct contact with the Imam whose place of residence was then unknown to most of them, Mirza began to lead the community autonomously.

Settlement in India

Imam subsequently travelled to various cities in the Indian subcontinent eventually settling permanently, in 1848, in Bombay (now Mumbai), which had the largest settlement of Khojas. This began the modern phase in the history of the Nizari Ismailis, and an era of regular contact between Imam and the widely dispersed communities. Imam began to take crucial steps to consolidate the community.

Prior to Imam’s arrival in the subcontinent, the Khojas had been rather autonomous. The management of the communal properties including jamatkhanas, as well as the collection of religious dues were “the responsibility of a select group of Khoja commercial magnates who formed a kind of council of elders (justi). In addition, the mukhi and kamadia as well as the sayyid/vakil, were central figures of authority …” (Asani, A Modern History of the Ismailis p 105).

Nizari Ismaili Tradition in the Subcontinent

The development of the Nizari Ismaili tradition in the subcontinent was associated with various da’is (pirs) who were sent, from the eleventh century on, by Imams residing in Persia, to teach Ismaili doctrines. These da’is referred to their teachings as Satpanth, ‘the true path.’ “Henceforth their followers identified themselves as Satpanthis rather than Ismailis. One of the mainstays of their devotional life was the singing of ginans composed by pirs and sayiyds in various local languages to convey the teachings of Satpanth in a manner which they could be best understood by the local population. They employed terms and ideas from a variety of Indic religious and philosophical currents, such as Bhaktis, Sant, Sufi, Vaishnavite, and yogic traditions to articulate its core concepts. As a result, the formulation of Satpanthi doctrine in the ginans was multilayered and multivalent in character” (More on ginans). Furthermore, in order to escape persecution, the community practiced taqiyya (precautionary dissimulation of beliefs) appearing externally as Sufis, Twelver Shi’i, or Sunni, participating in various rituals and ceremonies, hence making it problematic to define Khoja identity.

Soon after his arrival in Bombay, Imam Hasan Aly Shah began asserting his authority over all matters including control over communally owned property, a move which upset the upper echelons of the Khoja hierarchy (Ibid. p106).

Aga Khan Case

Some Khojas challenged Imam’s authority as a leader of the community, claiming he and the Khojas were Sunnis. The remote Nizari Ismaili communities in the subcontinent had established their own models of governance and forms of leadership. In addition, the British had established direct rule over most of the subcontinent seeking to govern a heterogeneous region by classifying the people based on religion. To clarify the situation for the Khoja Ismailis, Aga Khan I circulated a document in 1861, in Bombay and elsewhere, stating the Khojas were Shi’i Ismailis, and included the beliefs, customs, and practices, as well as his role as the leader of the community asking every Khoja to sign the document. He further instructed them that they no longer had to observe taqiyya as under British rule the exercise of all religions was free. The majority of the Khojas signed it, but a minority group challenged the Imam’s authority, claiming that the Khojas were originally Sunni and accused the Aga Khan of propagating ‘heretical’ ideas to bolster his authority.

Following several years of dispute, Imam’s opponents filed a legal suit, which came to be known as the Aga Khan Case, tried by Justice Joseph Arnould in 1866 at the Bombay High Court. The judgement “legally established the status of the community, referred to as ‘Shia Imami Ismailis’ and of the Imam as the murshid or spiritual head of the community and heir in lineal descent to the imam of Alamut” (Daftary, The Ismailis Their history & doctrines p 516). The ruling legally endorsed the Khojas as a single united group of the Raj, whose leader’s role was to govern their affairs and define their religious practices. The ruling was profound, considering that only a few decades earlier, Imams and members of the community were living in concealment. Unable to accept this judgement, the Aga Khan’s opponents joined the Sunni fold, calling themselves Sunni Khojas. (Asani, A Modern History of the Ismailis p 106).

During the three decades of his residence in the subcontinent, Imam Hasan Ali Shah organised the community through a network of officers, the mukhi and kamadia for jamats of a certain size. He also attended jamatkhana in Bombay on special occasions and led the public prayers of the Khojas. Every Saturday, when in Bombay, he held darbar, giving audience to the jamat.

Imam Hasan Ali Shah Aga Khan I died in 1881 after an eventful Imamat of sixty-four years, and was buried at Hasanabad in Bombay, where there is also a jamatkhana in the courtyard. He was succeeded by his son Aqa Ali Shah Aga Khan II.

Adapted from “From Satpanthi to Ismaili Muslim: The Articulation of Ismaili Khoja Identity in South Asia,” by Ali Asani published in A Modern History of the Ismailis Ed. by Farhad Daftary, I.B. Tauris, London, 2011

Contributed by Nimira Dewji, who also has her own blog – Nimirasblog – where she writes short articles on Ismaili history and Muslim civilisations.

Sources:

Memoirs of the First Aga Khan, Edited and Translated by Daniel Beben and Daryoush Mohammad Poor, I.B. Tauris, 2018

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, “The Khojas and Satpanth Ismailism,” The Ismailis: An Illustrated History, Azimuth Editions

Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, Cambridge University Press, 1990

Well summarized history. Every Ismaili is expected to know our history.

LikeLike

Yaalimadad.Enjoy the artic

LikeLike