The foremost Ismali jurist and founder of Fatimid Ismaili legal system al-Qadi al-Nu’man was born in 903 in Qayrawan, North Africa, into a learned family. He entered the service of Fatimid Caliph-Imam al-Mansur in 925, serving the Fatimids for fifty years until his death.

Named after the Prophet’s daughter, the Fatimids, Mawlana Hazar Imam’s ancestors, established their empire in 909 in North Africa when Imam al-Mahdi was proclaimed Caliph. The Fatimid Caliphate remained in North Africa during the reign of Imams al-Mahdi (r. 909-934), al-Qa‘im (r. 934-946), and al-Mansur (r. 946-953). In 973, Imam al-Mu’izz (r. 953-975) transferred the capital of the empire to Cairo, a city he founded. Al-Nu‘man accompanied Imam al-Mu‘izz to the new Fatimid capital, where he died in 974.

The Fatimids were confronted with a practical problem of statehood as there did not exist an Ismaili legal system with which to govern the state and its diverse citizens. In earlier times, the Ismailis had to conceal their beliefs and identities in order to escape persecution, observing the law of the land wherever they lived. The process of codifying Ismaili law began during Imam al-Mahdi’s reign, although Ismailism was never imposed on all subjects of the state.

In 948, Imam al-Mansur appointed al-Nu’man to the position of chief judge of the state. Imam al-Mu’izz, who composed a number of epistles himself, confirmed al-Nu’man’s status as chief judge, also entrusting him with the grievance proceedings throughout the Fatimid caliphate. Imam’s letter of investiture stated:

“In your decision and judgements, you should follow the Book of God… if you do not find in the Book any text [concerning an issue] nor any decision in the sunna of the Amir al-Mu’minin’s forefather, Muhammad, the messenger of God…then seek it in the madhab of the imams from the progeny of the Prophet. If a matter appears uncertain or baffling to you, refer it to the Amir al-Mu’minin and he will guide you to the proper decision”

(Jiwa, Towards a Shi’i Mediterranean Empire, p 27).

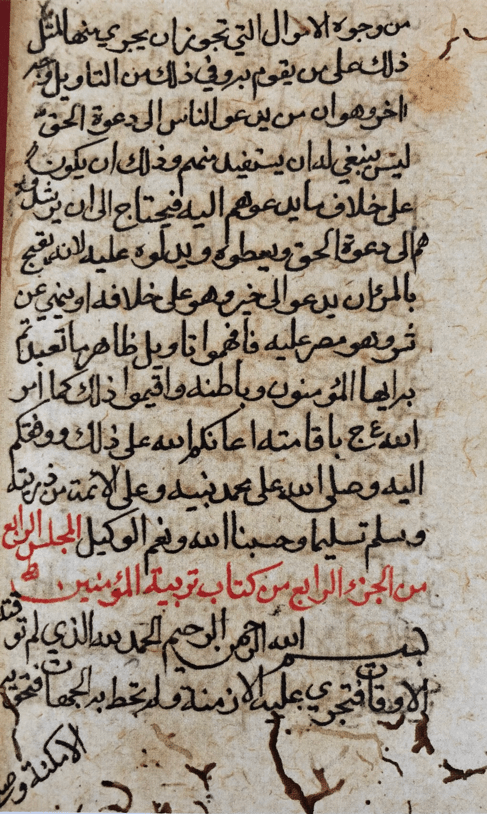

Under the Fatimids, the chief judge was also responsible for the da’wa activities. Thus, the “responsibilities for explaining and enforcing the zahir or the letter of the law and interpreting its batin or inner meaning, were united in one and the same person under the overall guardianship and guidance of the Imam of the time” (Daftary, A Short History of the Ismailis, p 76).

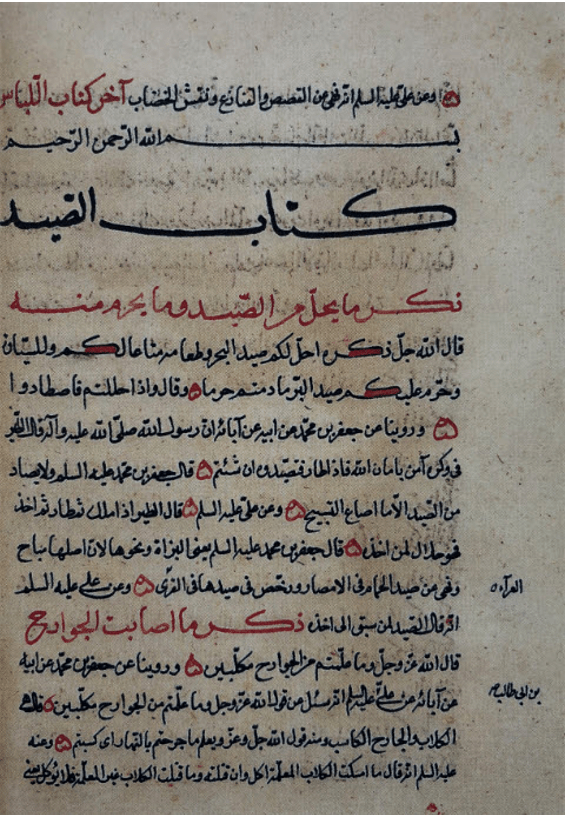

Centred on the Shi’i doctrine of Imamat, Al-Nu’man “codified Ismaili law by systematically collecting the firmly established legal hadiths transmitted from the ahl al-bayt“ (Daftary, A Short History of the Ismailis, p 76). He produced the compendium Kitab al-idah, his first legal work, which has not survived except for one small fragment. He also compiled (Kitab al-himma fi adab atba al- a’imma (The Book of Devotion: The Good Manners of the Followers of the Imam), in which he conveys “the fitting conduct towards the imam and above all in the presence of the imam […] It is a text of only four pages, but it includes all the principles of the Ismailis’ learning tradition” (Halm, The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning, p 61).

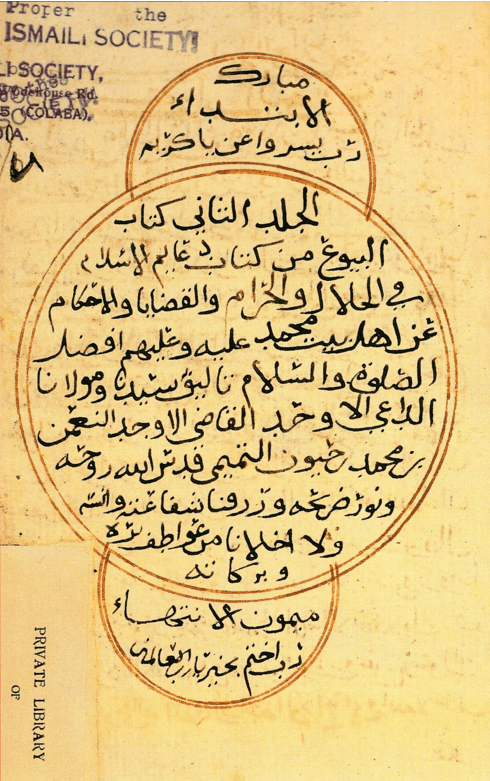

Al-Nu’man’s efforts culminated in the Da’a’im al-Islam (Pillars of Islam), which was closely supervised by Imam al-Mu’izz and endorsed as the official legal code of the Fatimid state. Imam al-Mu’izz “urged everyone to study and copy the Da’a’im, also read regularly at the majalis al-hikma” (sessions of wisdom). (Daftary, A Short History of the Ismailis p 77).

The shari’a, according to the Ismaili interpretation, provided the legal basis for the daily life of Muslim subjects. However, the Ismaili legal code was new and its principles had to be explained to all citizens, which was done in regular public sessions held by al-Nu’man on Fridays after mid-day prayers. The esoteric or batin sessions, majalis al-hikma, catered to Ismailis only, including women, were held at the Fatimid palace. The lectures delivered by al-Nu’man, and later by his successors, were approved by the Imams beforehand. Some of al-Nu’man’s lectures were collected in his Ta’wil da’a’im al-Islam (Hermeneutics of the Pillars of Islam) comprising 120 chapters of majalis.

Al-Nu’man wrote more than forty treatises on law, Ismaili doctrines, and history including the Iftitah al-da‘wa (Commencement of the Mission) which narrates the background to the establishment of the Fatimid state.

His Kitab al-majalis wa’l musayarat (Audiences and Rides) “is an eye-witness account of 292 audiences with the Fatimid imams, … mainly al-Mu’izz. It therefore, constitutes a remarkable account of the imam in action, facing the constant duty of receiving his followers, counselling them and ruling on all manner of issues brought before him.”1

It was largely due to the distinguished scholarship of al-Qadi al-Nu’man and his mentor al-Mu’izz that a comprehensive legal code was established that could effectively administer the range of faith communities inhabiting the Fatimid empire (Jiwa, Towards a Shi’i Mediterranean Empire, p 27).

Upon al-Nu’man’s death, Imam al-Mu’izz “led the prayer and laid him to rest on his side in the coffin. He was buried in his own house in Cairo” and “is reported to have eulogised his illustrious contributions to the Fatimid house by pronouncing the following:

Whoever presents a tenth of what al-Nu’man has accomplished, I guarantee him paradise on behalf of God.‘2

This tradition of serving the Fatimid cause with distinction was continued by the subsequent generations of al-Nu’man’s family: two of his sons, two grandsons and one great-grandson served as chief qadi and chief da’i in the Fatimid state, although there was no major development subsequently in Ismaili law. (Jiwa, Towards a Shi’i Mediterranean Empire, p 120, n. 338).

The Da‘a’im has continued throughout the centuries to serve as the principal legal text for the Tayyibi Musta‘li branch of Ismailis, including the Ismaili Bohras of South Asia.

1 Walker, Exploring an Islamic Empire, p 138 cited in Towards a Shi’i Mediterranean Empire p 27, n 65

2 Idris, Uyun, p 569 cited in Towards a Shi’i Mediterranean Empire p 120, n 338

Sources:

Farhad Daftary, A Short History of the Ismailis, Edinburgh University Press, 1998

Heinz Halm, The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning, I.B. Tauris, 1997

Shainool Jiwa, Towards a Shi’i Mediterranean Empire, I.B. Tauris, 2009

Contributed by Nimira Dewji. Nimira is an invited writer although she has contributed several articles in the past (view previous articles). She also has her own blog – Nimirasblog – where she writes short articles on Ismaili history and Muslim civilisations. When not researching and writing, Nimira volunteers at a shelter for the unhoused, and at a women’s shelter. She can be reached at nimirasblog@gmail.com.

Very informative Like to read again & again.

LikeLike